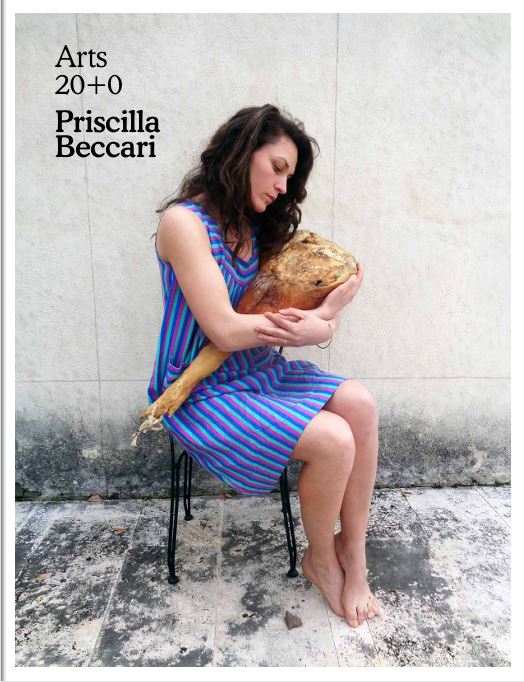

Priscilla Beccari’s work explores the human condition, particularly the feminine, through various media: video, installation, drawing, and more.

After studying Painting at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Tournai (Belgium), P.B. has participated in significant projects such as the exhibition for the Pavilion of San Marino at the Venice Biennale (2017), her first public sculpture in Mons (Belgium, 2023), and a collaboration with Hermès Faubourg Saint-Honoré for the scenography of their windows (Autumn 2024).

Her work highlights the body as a vehicle for symbolic expression, questioning the tensions between the intimate and the political, while reinterpreting ancient archetypes in the light of contemporary realities.

///

Le travail de Priscilla Beccari explore la condition humaine, particulièrement féminine, à travers divers médiums : vidéo, installation, dessin,…

Après des études à l’Académie des Beaux-Arts de Tournai (BE) en Peinture, P.B participe à des projets marquants, tels que l’exposition pour le Pavillon de Saint-Marin à la Biennale de Venise (2017), une première sculpture dans l’espace public à Mons (BE, 2023), et une collaboration avec Hermès Faubourg Saint-Honoré pour la scénographie des vitrines (Automne 2024).

Son travail met en lumière les corps comme vecteurs d’expressions symboliques, interrogeant les tensions entre intime et politique, tout en réinterprétant les archétypes anciens à l’aune des réalités contemporaines.

CV

à télécharger

Portolio

Monographie Art+20, La Médiatine, Benoit Dussart, 2020

Priscilla Beccari’s work unfolds slowly, through images, actions, and forms that echo or are the precursors to others. This constantly evolving universe embraces stylistic ruptures and a variety of registers, identifying itself at the crossroads of a carnivorous eroticism, a yellow-vested feminism, a sense of absurdity spiced with a touch of fear. It speaks of domestic boundaries and animality, suitcase-women and lifeless bodies, collapses and insolence.

Drawing is the epicenter of her practice, but it should not be reduced to that. While the density of the lines, the format, and the handling of the materials impress, the works on paper are only part of a broader approach that, in its harshest or lightest aspects, systematically cultivates unease, suffering, and strangeness. One often thinks of surrealism and the bitter irony of Buñuel’s later films, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and even more The Phantom of Liberty: apparent lightness, eccentricity lodged in the heart of daily life, a symbolic bestiary, the emergence of flesh, the ethereal presence of death. More fundamentally, perhaps, the work is part of a tradition that, from Louise Bourgeois to Kiki Smith, makes the body both a phantasmagorical and political support.

Mutated, dismembered, vulnerable, sometimes outrageously sexualized, the bodies are often those of lovers, of childhood, of labor… They no longer belong to themselves. They associate with floors or walls, they cover surfaces, inscribing themselves as elements among others, just as mute and frozen. The large-scale drawings form architectures more than they stage them. The paper extends or is patched together depending on the desired vertigo: perspectives twist, surfaces blur. The elasticity of the spaces and the amplitude of the void nurture a sense of isolation and solitude.

The subjects of these drawings are not the beings that inhabit them but the environment in which they blend: kitchens, living rooms, bedrooms, or bathrooms. These familiar spaces have become anxiety-inducing, cannibalistic, and systematically enclosed. Some figures, however, escape the traps of domesticity: the Venuses, and then a parade of anthropomorphic characters, bird-men, rams, wolf-women… but their ambiguities place them in a liminal space, suspended at the border between dream and nightmare, indifferent and thus relatively frightening.

The boldness or stuttering of the lines, the rough treatment of the materials, and above all their dimensions, give these images a form of embodiment, directly engaging with the exhibition space. One can approach the whole from a distance, but everything invites deeper involvement: the viewer becomes a witness, a voyeuristic witness… There is a sort of trap, rather exquisite, to become part of this series of forms, to gradually detect the strangest aspects, to be surprised by the most crude details.

The solitary bodies, the lovers, and the bestiary are also found in smaller drawings or monotypes. The play on perspectives is less present here, replaced by an even more vivid radicality. One thinks of the woman unraveling, the child in the fridge, « Mom says I’m a bad girl… » The titles have the value of a signature and are sometimes incorporated into the drawing. Once again, the home is the site of alienation, food evokes death, and desire tortures.

The work on paper offers a reservoir of forms always susceptible to being activated through sculpture, photography, film, or performance. It is difficult to draw a sharp line between these different mediums. What links them recurrently is the staging of the artist’s body. Molded, photographed, or filmed… it becomes an object/sculpture that can be integrated into both public and private spaces. The Les Jambes series, which reproduces the artist’s lower limbs at full scale, could find a place in a park, a bush, or a stove. The choice of clothing and poses creates the illusion of dismembered corpses transported in pieces. While the too-small containers in which they are awkwardly concealed, and their arrangement in space, can be seen through the lens of dark humor and tragicomedy, they also reveal – a theme that runs throughout the work – the objectification of beings, reduced to the state of meat, instruments, prisons, or utensils.

The cleaning lady is a recurring figure in the artist’s work. She merges with her ballet, her apron, the home, and the sidewalk. Her gestures are Taylorist, her tools ergonomic. She does not spare herself in the obedient maintenance of the capital of others. She becomes part of the furniture, her presence does not disturb. In contrast to this figure of consented submission stands that of the monster, the animal. Emancipation here is not a gentle thing: it wrinkles, scratches, devours. Perhaps it is only a fantasy, an impossible thing. Perhaps the bodies will remain folded, stored, threatened, and enslaved… But Priscilla Beccari’s work does not lead to this dead end. It rather suggests, even if desperately and at the cost of a certain cruelty, what still resists in us.**